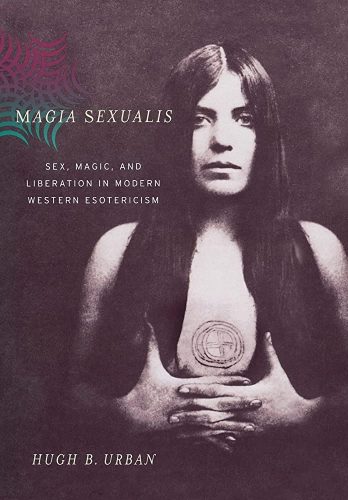

John Wisniewski is a writer who resides in New York. He has written for LA Review of Books, AMFM Magazine, Toronto Review of Books, and other publications. Hugh Urban is a professor of religious studies at Ohio State Universities Department of Comparative Studies. Focusing primarily on the traditions of South Asia, he is the author of Tantra: Sex, Secrecy, Politics and Power in the Study of Religion (2003) and Magia Sexualis: Sex, Magic, and Liberation in Modern Western Esotericism (2006), among other books. He has a strong secondary interest in contemporary new religious movements, and has published articles on Heaven’s Gate, Scientology and modern Western magic.

When did you begin studying religions?

I suppose I have been “studying” or at least thinking about religions from a very early age. I grew up in a fairly religious family, with an uncle, grandfather, and great-grandfather who were all priests in the Episcopal Church, and my own father became increasingly religious as he got older. So, I was sort of surrounded by religion from early on…but starting around my teenage years, I was also exposed to several alternative religions and various forms of occultism. Through my love of the Beatles, I became very interested in Hinduism and in Americanized versions of South Asian religions such as TM and ISKCON. And then when I was in high school, I used to spend hours and hours roaming the stacks of Penn State Library, where I would pull out the most obscure books on magic occultism, the paranormal, etc. that I could find. PSU library also happened to have a good collection of Aleister Crowley’s work in their Rare Books collection, which I also explored.

I suppose I have been “studying” or at least thinking about religions from a very early age. I grew up in a fairly religious family, with an uncle, grandfather, and great-grandfather who were all priests in the Episcopal Church, and my own father became increasingly religious as he got older. So, I was sort of surrounded by religion from early on…but starting around my teenage years, I was also exposed to several alternative religions and various forms of occultism. Through my love of the Beatles, I became very interested in Hinduism and in Americanized versions of South Asian religions such as TM and ISKCON. And then when I was in high school, I used to spend hours and hours roaming the stacks of Penn State Library, where I would pull out the most obscure books on magic occultism, the paranormal, etc. that I could find. PSU library also happened to have a good collection of Aleister Crowley’s work in their Rare Books collection, which I also explored.

When I was in college at George Washington University, I became exposed in a more academic way to the study of religion, and I became especially interested in Hinduism and Buddhism. This led me to do a study abroad program in India in 1988, where I lived in a Buddhist monastery in Bodh Gaya, the site of the Buddha’s enlightenment. I also had an opportunity to travel around South Asia, explore various holy sites, meet the Dalai Lama, etc. So that sort of got me hooked on the study of India, and I ended up studying Sanskrit and Bangla in graduate school at University of Chicago, where I received my MA and PhD. I have returned to India, Bangladesh, and Nepal dozens of times over the last 30 years for various research projects, as Hindu Tantra in northeast India (Bangla and Assam) became one of my primary areas of research.

At the same time, in addition to my interests in South Asian religions, I have always had strong interests in new religious movements, magic, neopaganism, and occultism. I have always followed scholarship in these areas, taught this material in my courses, and over time began publishing more on these topics.

What attracted you to the occult, to write about it?

If I were to be very honest, I would have to say that what first attracted me to the occult when I was younger was the general allure of the hidden, the mysterious, and the unknown (in my book on Secrecy, I call this “the seduction of the secret,” or the sort of erotic allure of what is hidden, veiled, or concealed). This interest in things secret, occult, hidden, and esoteric has remained with me throughout my entire academic career and sort of the driving question behind most of writing. However, it was really during my years as a graduate student at University Chicago and during my dissertation research that I began to think about the larger historical questions surrounding the occult. For example, why did occultism emerge as such a huge body of literature in Europe, England, and America during the 19th century (an era we usually think of as increasingly rational, scientific, and industrialized)? Why has there been such an intense resurgence of interest in the occult in our era, as we see in the wild proliferation of series on Netflix that deal with the supernatural, spirit possession, Satanism, Ouija boards, “cults,” etc.? And does this concept of “the occult” in modern European and North American history map onto esoteric traditions in other cultures, such as Hindu and Buddhist Tantra in Asia? What broader cross-cultural comparisons can we make about “occultism” as a cross-cultural or trans-historical phenomenon?

Could you tell us how the Church of Scientology began?

The origin of Scientology is a huge and complex question — indeed, one could write an entire book on the subject…(!) Anyway, here is sort of a thumbnail sketch of the basic story: Scientology was founded by L. Ron Hubbard, a man who was best known in his pre-Scientology days as a tremendously prolific author of science fiction and fantasy stories. Indeed, Hubbard was probably the most prolific author during the golden age of Sci Fi, writing so many stories that he had to publish them under a wide variety of pseudonyms, often appearing in the same issue of a magazine. Hubbard also has some involvement in occult and magical groups in California after World War II (though this is a long and controversial story for another day….). In 1950, Hubbard turned his attention from science fiction to a new science of the mind that he called “Dianetics,” which first appeared as an essay in the magazine Astounding Science Fiction. Derived from the Greek words dia (“through”) and nous (“mind”), Dianetics claimed to explain how the human mind works, the source of all psychological and psychosomatic problems, and the means to cure them. Dianetics centered on a therapeutic process called “auditing” in which a therapist (the “auditor”) would ask a series of questions of the individual (the one “audited”) in order to identify memories of pain or less (called “engrams”) talk through them and so “clear” them from the individual’s mind. When all the negative memories traces or engrams were removed, the individual would achieve a state called “Clear,” which Hubbard claimed to be a state of optimal psychological and physical well-being. While it was initially very successful as one of the first popular self-help fads in modern America, Dianetics never claimed to be “religious.”

In 1953, however, Hubbard established the Church of Scientology, which did make a more explicit claim to being a “religious” entity. The reasons for this shift were several. First, Hubbard claimed that many individuals during auditing were recalling past life experiences, sometimes from centuries past and on distant planets. This led him to develop the idea of a “thetan” or immortal spirit, that is immortal and reborn lifetime after lifetime. Scientology still uses the technique of auditing, but it involves not just clearing engrams from this lifetime but from past lifetimes, as well. Second, Dianetics had begun to be investigated by the Food and Drug Administration and by various state medical boards because it was making claims about physical healing through auditing. By shifting in the “religious” direction, Hubbard could claim to healing people in a spiritual sense rather than a physical one and so one no longer be subject to scrutiny by the FDA and others. Then later in the 1960s, a third reason he moved aggressively in the “religious” direction was because of tax exemption. The Church of Scientology had initially been registered as a non-profit religious entity in the mid-1950s, but that status was stripped by the IRS once it began scrutinizing the church’s finances more closely. This resulted in a 25-year war between the church and the IRS that involved literally thousands of lawsuits. During that period, Scientology made explicit efforts to present itself in a more religious light, with auditors wearing clerical collars, crosses being displayed prominently in Scientology centers, and so on.

During the late 1960s, Hubbard also introduced a series of increasingly complex and esoteric levels of auditing called Operating Thetan or OT. An Operating Thetan is a spiritual being that is increasingly free of the material world and is believed to acquire a variety of super-powers, such as telekinesis, telepathy, and the ability to “exteriorize” or travel outside the physical body. One of the most controversial OT levels is OT III, which reveals the complex history of the universe and the human condition. Though ostensibly confidential, it was leaked during the 1990s and widely circulated online. It was also the subject of an episode of the American TV show South Park in 2005.

Obviously, much more could be said about the complex origins of Scientology, but that’s sort of the Cliff Notes version.

Please tell us about writing Magia Sexualis

Magia Sexualis developed naturally as the logical follow-up to my book Tantra (2003). In the latter book, I examined the Tantric tradition and the ways it had been represented and often misrepresented in both modern scholarship and popular literature. Basically, I was asking the question of how Tantra was transformed from a highly esoteric religious practice focused primarily on spiritual and material power into a popularized practice now advertised as “spiritual sex” and “nookie nirvana”? In other words what were the complex historical, political, and cross-cultural dynamics that resulted in best-selling paperbacks such as The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Tantric Sex?

Magia Sexualis developed naturally as the logical follow-up to my book Tantra (2003). In the latter book, I examined the Tantric tradition and the ways it had been represented and often misrepresented in both modern scholarship and popular literature. Basically, I was asking the question of how Tantra was transformed from a highly esoteric religious practice focused primarily on spiritual and material power into a popularized practice now advertised as “spiritual sex” and “nookie nirvana”? In other words what were the complex historical, political, and cross-cultural dynamics that resulted in best-selling paperbacks such as The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Tantric Sex?

During that research, I found that the history of South Asian Tantra often intersected in various ways with esoteric traditions emerging in Europe, England, and the U.S. Tantra was a central influence on modern occult groups such as the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.), on Aleister Crowley and students, on Traditionalist authors such as Julius Evola, and even on Gerald Gardner and modern Wicca.

So, all of this led me to write Magia Sexualis, which examines the role of sexual practices in modern esoteric traditions from the nineteenth century to the present, many of which were influenced in various ways by Tantra, yoga, and other practices coming from the “mystic Orient.” In the nineteenth century, I argue, older esoteric currents from Hermetic, Gnostic, and Kabbalist traditions merged in complex ways with Tantra and other currents from the East, as well as with new ideas developed in psychoanalysis, among other things. All of this led to a specific practice of sexual magic, in which sexual union is not simply a symbol of mystical experience or oneness with God but an active technique used to harness sexual energy and direct it toward specific magical ends. The book looks at a series of key figures from the mid-nineteenth century to the present, including the mixed-raced Spiritualist author Paschal Beverly Randolph, the German occultist Theodor Reuss, the British magus Aleister Crowley, the Italian traditionalist Julius Evola, the British founder of modern Wicca Gerald Gardner, modern Satanists such as Anton LaVey, and Chaos magicians such as Peter Carroll. Ultimately, I argue that the history of modern sexual magic is much more interesting than just the story of an obscure occult practices but in fact gives us profound insight into many larger cultural and religious changes that have taken place in European and American societies over the last 150 years. In particular, this history gives us deep insight into our larger cultural obsessions with sexuality and consistent attempt to link social and political freedom to sexual freedom.

Does the O.T.O. have a history of using sex magic as part of their rituals?

The Ordo Templi Orientis was founded in Germany and Austria in the early twentieth century. One of its primary inspirations was Carl Kellner, a wealthy Austrian industrialist who had a strong interest in Hindu yoga and Tantra; and its primary organizer was Theodor Reuss, a German occultist and Freemason who borrowed heavily from Gnosticism in addition to Eastern sources. The O.T.O. was also likely influenced by ideas of sexual magic developed by the American Spiritualist, Paschal Beverly Randolph, and by European esoteric groups such as the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor. From its earliest publications such as the journal Oriflamme in 1904, the O.T.O. claimed to possess the secrets of sexual magic, which it claimed would explain “all the riddles of nature, all Masonic symbolism, and all religious systems.”

The most influential leader of the O.T.O. was the British occultist, Aleister Crowley, who first came into contact with Reuss in 1910 and was named the head of the order in Britain and Ireland. Crowley had a strong interest in the practice and uses of sexual magic, which he described in his autobiography as “a scientific secret,” one so powerful that if perfectly understood “there would be nothing which the human imagination can conceive that could not be realized in practice.” Crowley also made sexual practices a central part of O.T.O. practice and grades of initiation. In Crowley’s revised system of initiations, the O.T.O. was organized into eleven grades, the eighth, ninth and eleventh of which focused on sexual practices. The eighth degree involved auto-erotic acts, the ninth heterosexual rites, and the eleventh mostly homosexual rites. It seems significant that Crowley would make acts such transgressive as masturbation and same-sex key parts of his magical system, at a time in England when masturbation was widely believed to cause insanity, and homosexuality was not only considered pathological but was still quite illegal. The power of transgression or the deliberate overstepping of social, moral, and religious taboos seems to have been a key part of the tremendous magic power that Crowley associated with such acts.

Why do secret societies practice rituals in secret? Do secret occult societies often wield great power?

As I have tried to argue throughout my various writings on the subject, there is no one reason why groups practice secrecy; rather, secrecy is more like a sociological strategy that can be used for many, many different ends (this is also a point that the sociologist Georg Simmel long ago made in his famous essay on secrecy and secret societies). In some cases, secrecy can be a tool used by elites to mystify their power and status, making themselves appear more awesome and formidable; yet in other cases, it can be used by marginal and subversive groups to escape persecution under authoritarian political regimes; and in still other cases, it can be used revolutionary and/or terrorist groups to conceal their activities and engage in acts of violence. In some historical cases, secret societies have wielded great power (for example, Freemasons in many periods of American, British, and European history); and in other cases, they have used the tactics of concealment to challenge and attack system of power (for example, terrorist organizations such as al-Qaeda or white supremacist groups such as the Brüder Schweigen).

In my Secrecy book, I outline six different modes or uses of religious concealment, each illustrated by one historical example. I call these six modes: 1) the adornment of silence, or the role of secrecy as a source of status, prestige, and symbolic capital; 2) the advertisement of the secret, or the paradoxical display of the claim to possess esoteric knowledge; 3) the seduction of the secret, or the sort of erotic play of concealment and disclosure, veiling and unveiling that characterizes many esoteric traditions; 4) secrecy and social resistance, or the role of concealment in protecting groups that might be marginalized or persecuted by the dominant social-political order; 5) the terror of secrecy, or the use of concealment as a tactic of religious violence and terrorism; and 6) secrecy as an historical process, which often changes dramatically over time in shifting social, political, and historical contexts.

What will your next book be about?

I just finished a book called The Path of Desire: Living Tantra in Northeast India, which should be out later in 2023. The book examines lived and popular forms of Tantric practice in Assam, a region that is often cited as the original homeland or heartland of Tantra. Since at least the eighth century, Assam (or Kamarupa as it is known in early sources) has been identified as the site of the goddess’ yoni or sexual organ, making it the figurative and perhaps literal “womb of Tantra.” And it remains a lively center of Tantric practice to this day. In the book, I examine the full spectrum of living forms of Tantra, which include not only the more elite, Sanskrit forms that we see in major temple complexes but also the more popular and folk aspects of Tantra. These include practices such as spirit possession, dance, animal sacrifice, and a wide range of both benevolent and malevolent magic.

Is there a dark side to occult secret societies?

I suppose it depends on what one means by “dark”… but there are certainly many links – both real and imaginary – between secret societies and problematic political movements. Some of these links are mostly the product of paranoia and conspiracy theories (“Freemasons are running the country!” “the Illuminati are secretly controlling the world!”, etc.); but some are real historical connections. Nicholas Goodricke-Clarke has written two excellent books on the complex links between occultism and far-right politics, particularly Nazism and other forms of fascism. Some of the most influential right-leaning scholars of the twentieth century were deeply immersed in the study of esotericism and occultism; perhaps the clearest example is Julius Evola, the controversial Traditionalist author who wrote extensively both on politics and on various aspects of magic, Tantra, yoga, and the metaphysics of sex. In the United States and elsewhere today, there are also numerous white-supremacist occult groups, such as certain forms of Odinism and other far-right neo-pagan movements.

The reasons for these links are not far to seek. Occultism typically involves a quest for various kinds of power – both spiritual and material – and that power may lend itself to darker sorts of uses in this world. There is also a natural connection between secrecy and power. Secrecy allows groups to exchange ideas, organize, and act in ways that fly under the radar of law enforcement or public scrutiny. As the sociologist Georg Simmel pointed out, secrecy can enable small, marginalized groups to escape persecution by state or religious authorities; but it can also enable dissident groups to engage in acts of violence and terror. I discuss this latter point at length in my Secrecy book in the chapter “The Terror of Secrecy,” which focuses on the American white supremacist group The Brüder Schweigen or Silent Brotherhood.