Anton Bruckner Seen Through Schopenhauer’s Aesthetics

Jason Kiss

Schopenhauer’s Aesthetics and How it Fits into His Philosophy

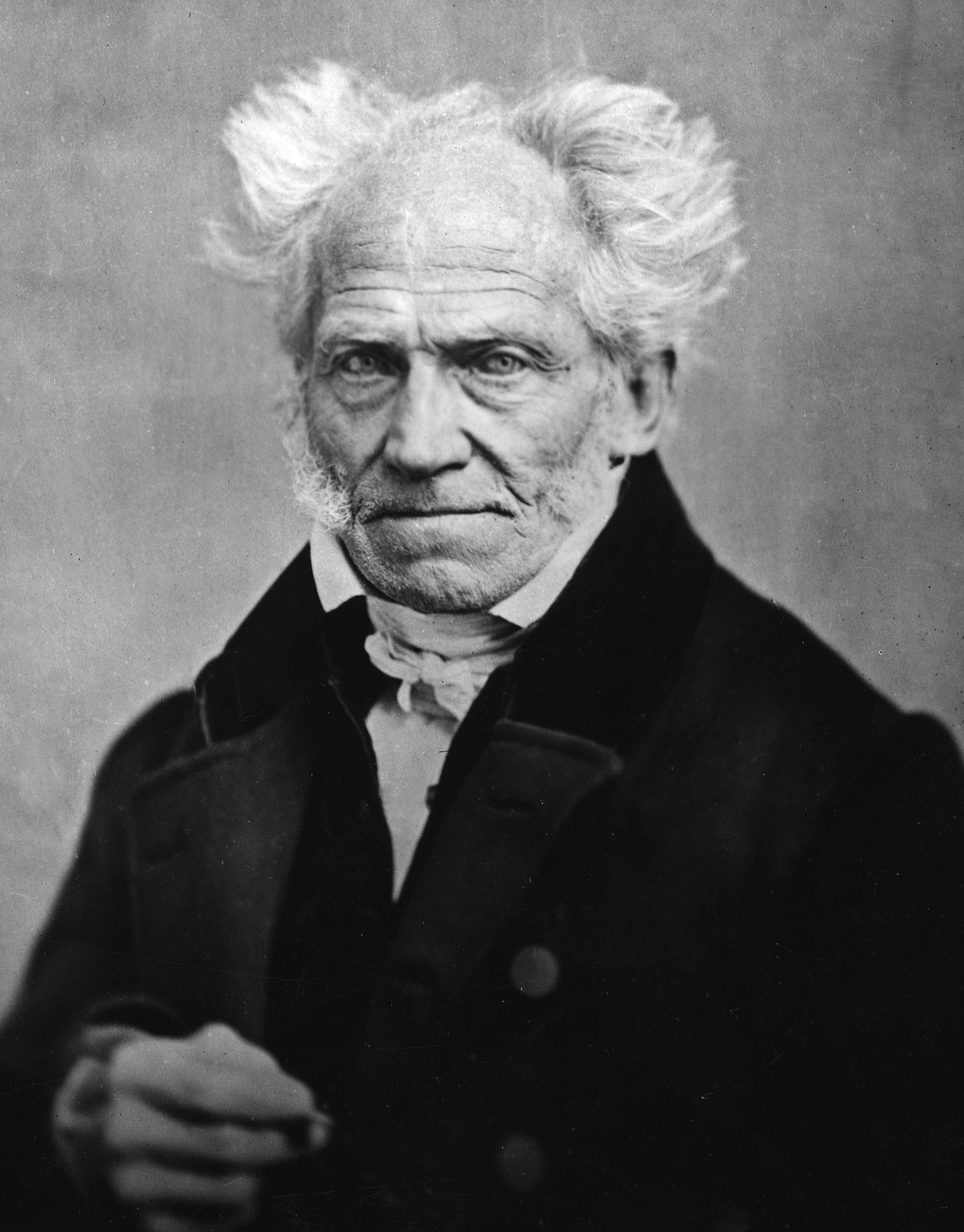

Arthur Schopenhauer’s aesthetic theory, as expounded in his work “The World as Will and Representation,” draws from the Platonic tradition where the material world is viewed with contempt and a “greater” reality lies beneath the surface.[1] Schopenhauer is often referred to as “the musician’s philosopher” due to his emphasis on absolute, non-programmatic music bearing the most metaphysical weight of all forms of artistic expression.[2] His aesthetics involve the idea that the greatest aesthetic experiences lead to a temporary negation of the will rather than portraying or embracing it.

Arthur Schopenhauer’s aesthetic theory, as expounded in his work “The World as Will and Representation,” draws from the Platonic tradition where the material world is viewed with contempt and a “greater” reality lies beneath the surface.[1] Schopenhauer is often referred to as “the musician’s philosopher” due to his emphasis on absolute, non-programmatic music bearing the most metaphysical weight of all forms of artistic expression.[2] His aesthetics involve the idea that the greatest aesthetic experiences lead to a temporary negation of the will rather than portraying or embracing it.

Clarifying Schopenhauer’s notion of the ‘will’ is important. Under the profound influence of Kant, Schopenhauer shared the belief that reality comprises two facets: the realm of phenomena, accessible to our experience, and the domain of noumena, the things-in-themselves that lie beyond sense perception. Differing from Kant, Schopenhauer championed the existence of a singular noumenon, an all-encompassing metaphysical thing-in-itself, which objectifies itself in the tangible world through a macroscopic will. He discerned an insatiable metaphysical will interwoven, especially, into human affairs and the natural world. Termed the will-to-live [der Wille zum Leben], this force is far from benevolent, as Schopenhauer ascertained. On the contrary, he saw it as inherently antagonistic to our overall well-being, often leading us into states of boredom and suffering.

Hence, the imperative arises to deny the will. Schopenhauer presented two approaches to release the enduring grasp of the will. The first involves asceticism, entailing the renunciation of earthly pleasures—a parallel to Stoicism’s inclinations. The second, a more pragmatic approach, involves immersing oneself in profound aesthetics, a realm in which absolute music shines the brightest and holds direct metaphysical weight.

Schopenhauer expounds on this notion, describing that absolute music has the potential to transport us beyond the routines and aspirations of our mundane existence. This transcendental experience bears a somewhat dissociative effect, propelling our consciousness beyond the realm of the observable to the realm of Platonic Ideas. The very encounter with “will-lessness” becomes a self-contained entity, nearing an independent existence not unlike the noumenon, thereby beckoning us closer to universal truth. Other artforms lack the same profundity, for they either replicate or depict objects tethered to the realm of mundane experience and, consequently, remain entwined with the will.

In short, Schopenhauer’s aesthetics fundamentally assigns the highest significance to what opposes the individual and their everyday desires. The ultimate objective is to experience a state of transcendence through engagement with absolute music; its sublimities being the most direct. This aligns with his broader philosophy, and its emphasis on self-negation shares similarities with other monist philosophies, such as Neoplatonism, Advaita Vedanta, and Mahayana Buddhism.

Addressing the Valkyrie in the Room

An abundance of literature delves into Schopenhauer’s influence on Richard Wagner and their relationship. A recommended read for a comprehensive understanding of the extent to which Wagner effectively integrated Schopenhauer’s ideas into his music is the book “Wagner and Schopenhauer: A Closer Look,” by Milton E. Brener. Bringing up Wagner is essential, given his substantial impact on Anton Bruckner, especially in terms of chromaticism. Not acknowledging this connection would be a deficiency. Schopenhauer’s conviction in the supremacy of absolute, non-programmatic music is evident, while he also acknowledged the admissibility of opera libretti in a secondary, supporting role rather than the central focus.[3]

Anton Bruckner Seen Through Schopenhauer’s Aesthetics

Unfortunately, Schopenhauer passed away in 1860, a couple of decades before Anton Bruckner’s rise to fame. While Schopenhauer did not have the privilege of experiencing the music of Bruckner or that of many of his contemporaries, his musical predilections, especially his approbation for Ludwig van Beethoven, offer a gateway into interpreting his aesthetic theory in the realm of what would become Romanticism. Schopenhauer perceived Beethoven’s music as a violent tempest of emotions, a severe portrayal of human expression in its most turbulent and fiery form. He also saw transcendental value in this emotional severity, an element that would later become the hallmark of Romanticism.

Bruckner, the high priest of Romanticism, held a profound reverence for Beethoven, a sentiment evident in his own symphonies. He closely followed Beethoven’s model, incorporating cyclic sonata forms, expansive structures, groundbreaking and complex harmonic explorations, and intense emotional expressiveness, where a sense of struggle is ultimately overcome. However, Bruckner’s symphonies elevate these elements to even grander proportions. His breadth of compositional knowledge was more extensive than Beethoven’s, spanning from Wagnerian chromaticism to old church modes. Moreover, Bruckner’s symphonies are on a much larger scale, both in terms of duration and orchestration, and their codas tend to be more extended and intense compared to Beethoven’s. In fact, they often possess a majestic quality. When contemplating them, one can only speculate about Schopenhauer’s potential response; however, they would certainly serve to reinforce his perspective that the sublime qualities inherent in absolute music stand as the most unmediated manifestations of transcendental experience.

As such, it is hard to imagine Schopenhauer denying Bruckner as he did Wagner. The only potential issue might be Bruckner denying Schopenhauer. The composer’s devout Catholicism appears to be at odds with the philosopher’s aesthetic theory, as Bruckner’s faith would have embraced the material world as God’s creation, not something which should be renounced, especially not through music. However, both Schopenhauer and Bruckner shared a common ground in their unwavering appreciation of the transcendental potential of music. Bruckner’s symphonies are often described as spiritual voyages where listeners are invited to explore the ethereal and transcendent aspects of reality through the medium of absolute music. In this regard, both Schopenhauer and Bruckner recognized that absolute music has the unique capacity to transcend the limitations of words and concepts, allowing us to access profound transcendental states. While differing in worldviews, they unite in music’s transcendental potential.

Article by Jason Kiss, also known as ‘Lonegoat’ from the Necroclassical project Goatcraft, originally published in the November 2023 edition of The Bruckner Journal (https://brucknerjournal.com/).

For enthusiasts of Anton Bruckner’s music, membership with the non-profit Bruckner Society of America also includes a subscription to The Bruckner Journal, as well as other perks. Visit their website at https://www.brucknersocietyamerica.org/ for more information.

[1] Schopenhauer, Arthur. “The World as Will and Representation, Volume I,” Chapter: 1, Dover Publications, Garden City, New York, 1969. Page 7

[2] Schopenhauer, Arthur. “The World as Will and Representation, Volume I,” Chapter: 52, Dover Publications, Garden City, New York, 1969. Pages 257-267

[3] Schopenhauer, Arthur. “The World as Will and Representation, Volume II,” Chapter: “On the Metaphysics of Music,” Dover Publications, Garden City, New York. 1969. Page 449